Experiences of the Great War: George Maynard Ward of Kibworth

George Maynard Ward, known as Maynard, was an ordinary Kibworth lad, the eldest of five children. He went to the Church School in the village until he was 12 or 13 and then it was out to work. In April 1917, now aged 18, he was passed fit for general military service and on 17 May, in his words, he was “called to the colours”. He records that he returned from Wigston that night in ‘civvies’ but the next day he and his friends returned ‘in khaki’. Despite the accounts that he must have seen in the papers or heard from older local lads about the war, he sounds proud to be joining up.

The young men were soon off to Rugeley Camp, Cannock Chase where they went on route marches, had weekly bathing parade at Horner’s Pool and had a go at firing guns on the big ranges up on the moors. In December Maynard and two other local lads were off to Yorkshire to join Major Hall’s Model Platoon (“a nice old chap”) and go on coast patrols and lighthouse guard.

He could have had little idea of what he was to experience next. The Germans, wanting to tip the scales in their favour on the Western Front before the arrival in force of American troops, were planning what became known as the Spring Offensive. Arriving in France in late March 1918, Maynard joined the 1/4th East Yorkshire Regiment in the trenches along the banks of the La Bassée canal. His journey there was interrupted by German shelling and civilians were fleeing from the villages he and his comrades passed through. The first night, in atrocious weather, through barbed wire and over shell holes, he and three others fetched rations from the limbers and the tea and bacon went down very well. But at midnight the Germans began a heavy barrage that lasted until daybreak. Then behind a smokescreen, and accompanied by gas, came thousands of Germans. They were held back until the order came “every man for himself”. Maynard and his comrades began to retire, digging in when they could, and then setting off again. He only comments, “what sights and sounds I saw I shall never forget; dead and wounded everywhere”. After three weeks, his regiment was relieved by the Royal Scots and the Indian Cavalry and they retreated to Aire through the blazing ruins of Estaires.

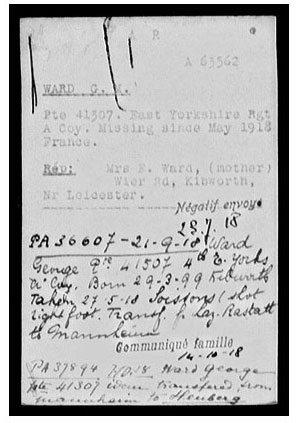

After some time in Aire, the men were on the move again. A long ride via Paris took them to Fismes, near Reims, where French guides showed them the way to the trenches. This was thought to be a quiet part of the Front but, on 27 May, a ferocious bombardment began, accompanied by gas shells, and then the German infantry advanced. There was fierce fighting and Maynard and his fellow soldiers were surrounded. Many were killed or taken prisoner that day. Maynard had been injured in the foot and was carried behind the German lines where his wound was dressed.

He writes simply, “the sights I saw behind those lines I shall never forget”. After being passed from one dressing station to another he ended up in hospital at Rastatt, near Karlsruhe. Conditions there were terrible: there were no dressings and food was limited to black bread and coffee for breakfast; soup of rotten apples, rotten fish or sauerkraut at midday; and black bread with jam and coffee for tea. With no cigarettes and no books to read, all they could do was lie there and hope for the best. Hundreds died and, when he could walk again, Maynard had the job of ‘laying out’ his dead comrades in their coffins.

Once his injured foot had healed, Maynard was sent further north to an internment camp at Mannheim. In the town, the shops were closed – there was nothing to sell. Conditions in the camp were bad; men slept on the floor of the huts with a single blanket and became infested with lice. Many died of dysentery. After six weeks, the PoWs were moved to another camp at Heuberg where they had their hair shaved off and were fumigated to get rid of the lice.

Finally, after a long train journey and a 30 kilometre walk, Maynard ended up on a farm near Herrischried deep in the Black Forest near the Swiss border. Here he worked from dawn to dusk, mowing grass and corn with a scythe, digging up potatoes and, in the winter, felling trees and sawing logs. He ate with the family although there was little to eat. The weather that winter was bad, with very deep snow. News was slow to reach that remote part of the German countryside. It was only on 6 December, almost a month after the signing of the Armistice, that Maynard learnt that the war was over. His journey home began with a 30 kilometre walk to the nearest station to catch the train to Freiburg and then to Mulhouse in France. Then “we were let loose to go where we pleased, we walked for miles by day and slept in old ruined houses or by the roadside at night”. Eventually he reached Belfort and was put into hospital by American troops there. After more journeying and hospital stays he finally made it home to Kibworth. However, after two months leave he found himself off again – this time to Ireland.

Once his army days were over, Maynard worked on the railways and later, with his brother, kept a small-holding on Weir Road. All his life he had liked to write, stories of his family, lists of sporting events and flowers that he grew, so it was natural that, in 1925, he sat down and recorded his wartime experiences. He had lived through two of the great German advances of 1918 in which so many others had died and had seen terrible things but, thanks to his account, we can understand a little of how much we owe to ordinary men like him.

Maynard mentions many local men who enlisted with him or whom he met during his war service. Len Dunkley, George Simons, Billy Grant and Joe Everett accompanied him to Wigston to enlist. During training he was with George Simons, Billy Nutt, H. Jordan, Albert Patrick, A. Martin (killed), J. Gilbert (killed), E. Ireland, G. Rayworth (the last 5 from Market Harborough), his best pal A. York (killed), J. Cockeril (killed) of Lubenham. He also saw H. Timson, Bill Lovatt, Bill Grant, Jack Truett, Austin Copeland (both killed) and C. Butteriss. At Brocton Camp he was trained by Jack Brown from Tur Langton; he also saw George Lee, Dick Holyoak and Dennis Coleman from Kibworth. At Withernsea, he was accompanied by Albert Patrick and Norman Wilson.

If you recognise any of these names, and would like to share their stories, please contact the Chronicle.

The Chronicle would like to thank Eileen Bromley for sharing the account written by her uncle Maynard of his experiences in the Great War.

JME

Women in the Great War

Women in the Great War